Post-Consumer Life

The lifespan of a shoe continues after the wearer has decided it’s useful life is over. It’s important to factor this in, because the most likely destination of a used shoe is a landfill site. Only a small proportion of shoes follow the alternative routes of reuse and recycling, and even then the ultimate endpoint is still landfill - it's just been postponed (rather than eliminated).

Waste

According to The Centre for SMART (Sustainable Manufacturing and Recycling Technologies), the waste arising from post-consumer shoes in the EU is estimated 1.2 million tonnes per year”. [1]

Where does this 1.2 million tonnes go? In the UK, approximately 15% (or 26,244 tonnes) of post-consumer shoe waste is collected and redistributed as secondhand. The remaining 85% (or 142,756 tonnes) is sent to landfill. [1] Why is this such a high proportion? Or to address the bigger issue, why are shoes being thrown away in the first place?

“In the UK, Oxfam alone with its shop donations and door-to-door collections recovers around 5-10 tonnes of worn or unwanted shoes every week.” [1] As a solution for avoiding post-consumer shoe waste, how successful is this? Sure, it’s a nice feeling to donate your unwanted clothing and footwear. But looking at it from another angle, how often do you buy second hand shoes? Many people stigmatise pre-owned items for being “unsanitary”. Whilst this problem with clothing can generally be solved with a run in the washing machine, footwear is a different story - secondhand shoes can be a little trickier to clean. The other issue with used shoes is that they tend to gradually adapt to the wearer’s foot shape, while the sole wears out in specific areas according to the wearer’s unique gait - which is unlikely to match another person.

Recycling & Recyclability

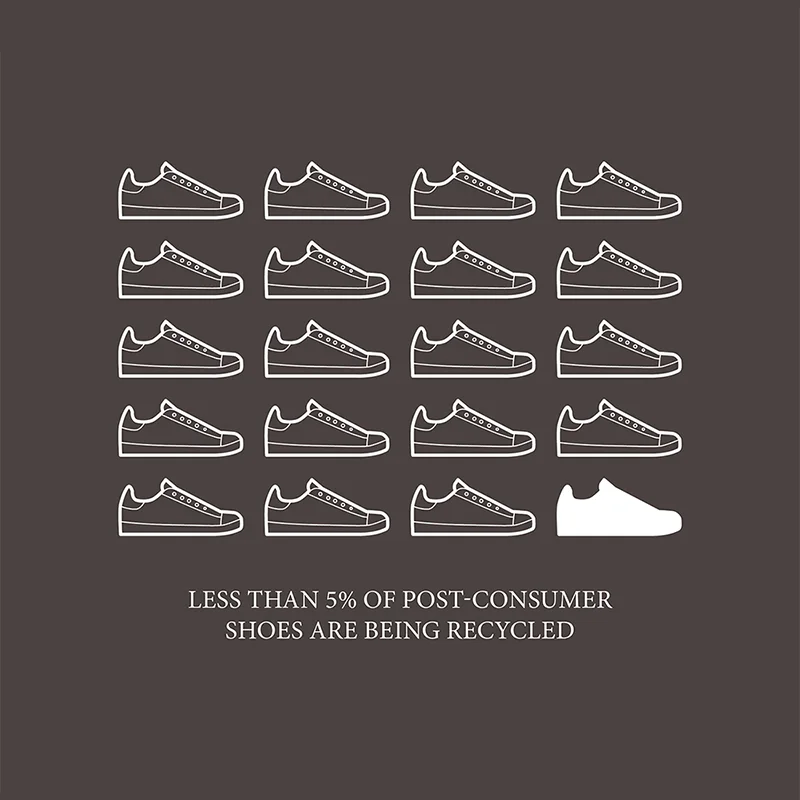

There’s a general lack of recycling, with less than 5% of the world’s end-of-life shoes being recycled. [2] This is partly because of the materials used. Nike recognises the importance of material selection as they revealed that materials account for about 60% of the environmental footprint of their shoes.” [3]

Most materials don’t have the necessary recycling facilities in place. Even leather which is highly durable and a popular material choice for shoes - “more than 60% of the UK shoe sales are leather-based shoes” [1] - yet the recycling of leather from post-consumer shoes has not been commercially exploited. [1]

Other materials can be recycled, and yet it's not happening. EVA foam is a case in point. According to recycling specialists, INTCO, “At present, the global ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA) recycling rate is generally very low. Recycling EVA foam companies are also very few.” [4]

Within any one pair of shoes, there’s a long list of materials: “Footwear is incredibly difficult to recycle as it can contain up to 40 different types of material, many of which are stitched or glued together.” [5] This makes it difficult to separate each of the different materials for recycling. The Centre for Sustainable Manufacturing & Recycling Technologies (SMART) at Loughborough University has already devised a footwear recycling system in 2013; they demonstrated shredding the shoes and automatically sort fragments by density. Although it seemed like a viable waste reduction solution, most of the materials can only be downcycled which drastically lowers their quality and value.

In 2017 FastFeetGrinded have launched in The Netherlands a recycling shoe facility which separates and converts them into various reusable materials, which are then repurposed into various products like playground surfaces, and even new shoe components. For example, Asics Neocurve which was released in 2024 contains about 20% recycled materials from FastFeetGrinded shoes.

But what if our shoes were built to be recycled? Planning how shoes can be recycled post-consumer use generally doesn’t come into the design process - it’s an afterthought. Permanent assembly methods such as glue (cemented shoe construction) which are quick and cheap to produce, are also extremely hard to repair, so these shoes tend to have a relatively short lifespan.

Another troubling example is Vulcanised shoes (often seen in classic plimsolls) which can’t be resoled because the upper, outsole and foxing tape bond together during vulcanisation, preventing them from being separated.

So, if certain assembly methods are difficult or impossible to recycle, why can’t we implement better strategies like design for disassembly?

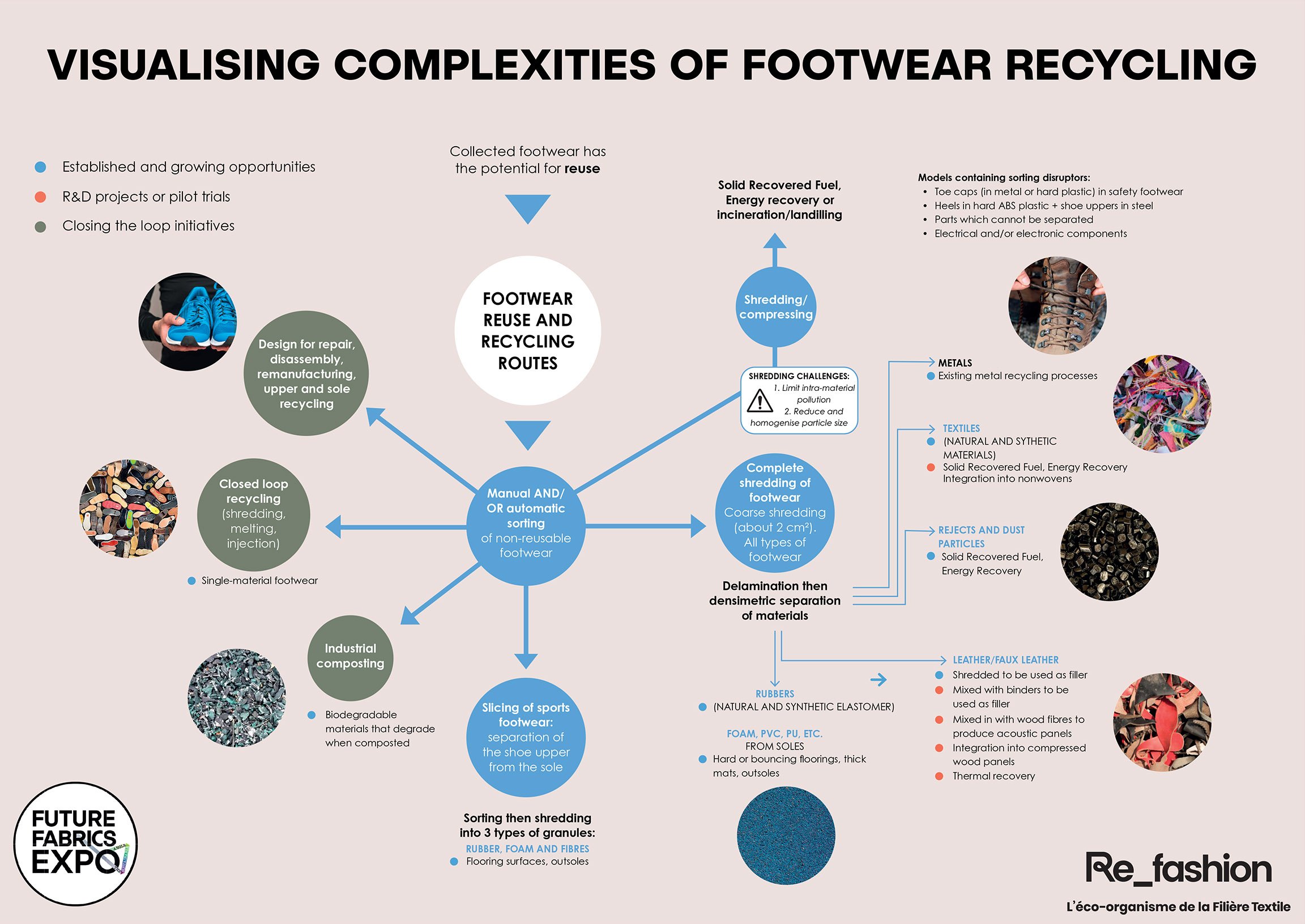

The mapping diagram here shows potential recycling roots, challenges, and opportunities associated with the recovery of both footwear and their materials, based on the current material complexity of most shoes. Recovery of intact reusable footwear for re-commerce via repair and redistribution networks aligns with the EU’s initiatives to prevent waste from going to Landfill in the first place.

This mapping by Future Fabric Expo, was adapted and fine-tuned in 2024, from an earlier version by ReFashion.

Biodegradability

Simple Shoes were one of the first brands to introduce a “BIO-D additive” in 2010, enabling their shoes to biodegrade within 20 years rather than 1,000 years.

Biodegradability is an important environmental parameter for the assessment of organic substances and its decomposition and mineralization by microorganisms in the environment.

One factor in establishing how a product will degrade, is the environment they are placed in at its end of life, its therefore essential to conduct biodegradability testing, not only to validate your claim but also to determent under what conditions it will biodegrade and how long it takes to breakdown.

Placing the product in the right condition is a vital part of the process and unless it’s clearly communicated, and actioned, its unlikely to work in a standard landfill - the most probable post-consumer scenario.

Its worth mentioning that biodegradable materials are not necessarily compostable. Although most materials can eventually break down, if they are made from manmade chemicals, they are likely to leave behind toxic residue. Whilst compostable materials release valuable nutrients into the soil, aiding the growth of plants.

How you achieve biodegradability matters. It’s far better to use natural materials - plant based, bio-based or biofabricated (and aim for the highest possible content), rather than combine microbial and enzymatic additive within the shoe components to aid decomposition. This technology only resolves a small part of the shoe lifecycle - it does not decrease the pollution from extracting raw materials or production processes.

Circular Economy

Within the design world, there are a number of terms centering around the idea that our waste shouldn’t be wasted e.g. circular economy, cradle to cradle or a closed loop system. The list goes on. But they all contain a combination of design practices like biomimicry and Design for Disassembly, placing them within one holistic system.

If we go by the WRAP definition, a circular economy is “an alternative to a traditional linear economy (make, use, dispose) in which we keep resources in use for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them whilst in use, then recover and regenerate products and materials at the end of each service life.”

The importance of nature within this kind of system is emphasised by this Ellen MacArthur Foundation explanation that states that cradle to cradle design “perceives the safe and productive processes of nature’s ‘biological metabolism’ as a model for developing a ‘technical metabolism’ flow of industrial materials.”

There are steps that could be taken to enable a circular economy to exist within the footwear industry:

Repairable manufacturing methods should be chosen over permanent methods e.g. vulcanisation. For example, the Goodyear Welt is a long lasting shoe construction method that is relatively easy to repair.

Quality materials e.g. natural rubber are needed to ensure that the waste can become food for the next cycle.

Refuse collection systems need to be in place. Some materials need certain criteria in order to biodegrade.

Very few examples of this thinking exist in today’s footwear industry, but there’s encouraging growing interest. The Circular Footwear Initiative lists circular shoe start-ups that incorporate circularity in their core business model, which include repair services and take-back schemes.

An interesting French brand Hodei integrates “deconstructable design” with recyclability. Not only their shoes are “returnable”, but their carbon footprint is impressively low, and they also provide a free open-source option to customise certain components for customers that have access to a 3D printer.

Larger established brands are starting to explore circularity too. Re:Suede is Puma's second attempt at launching a circular compostable shoe in 2021 (with the first coming over a decade earlier in the form of InCycle collection). In their experiment, 500 shoes were sent out to testers for six months of wear. Of those shoes, 412 were returned and sent to an industrial composting facility in The Netherlands, where they were mixed with other green waste and left to biodegrade. A large proportion of the leather trainer had broken down sufficiently to be sold in The Netherlands as Grade A compost – a high-quality compost typically used on gardens and landscapes. The TPE soles however took too long to break down. Following a report of the experiment's findings, Puma seem determent to pursue an improved compostable model in the future.

In 2019 adidas launched the Futurecraft.Loop, a mono-materiality shoe made from 100% TPU which is potentially fully recyclable and reusable. The idea is that once the shoes come to the end of their first life and are returned to adidas, they are washed, ground to pellets and melted into material for components for a new pair of shoes.

Looking for more examples? Check our list of sustainable design strategies.

The Footwear Collective

It's quite clear that the most effective and resourceful way to steer the industry towards the implementation of circular business models is by sharing knowledge and collaborating.

The Footwear Collective (TFC), founded in 2023, is an initiative that aims to promote circular practices in the footwear industry. Led by EarthDNA, a non-profit climate advocacy platform, TFC has brought together eight founding members (Brooks, Crocs, Ecco, New Balance, On, Reformation, Target, and Vibram) with the aim to collaboratively develop circular solutions and implement the required infrastructure.

What led to the creation of TFC were the learnings from Footwear Manifesto - a white paper from a MIT research project. The research encompassed an industry survey and a multistakeholder summit that brought together thought leaders from the footwear industry, waste management, investors, and government to discuss opportunities for footwear in the circular economy.

Their key findings were:

Today, the complexity of shoes — the design complexity, manufacturing process, and temporal use — is the biggest challenge to circularity at scale.

Companies have the will to change, but there is little strategic alignment on circularity across the footwear industry, and no common means of measuring progress.

Collaboration is vital for scaling circular systems — not just within the brands, but with a multitude of stakeholders including suppliers, infrastructure investors, government, academia, and entrepreneurs.

Building a circular dynamic system will require diverse solutions that open opportunities across sectors and communities.

Solutions

The entire lifecycle of a pair of shoes needs to be considered from the design process all the way to post-consumption. The best outcome can be created by using a number of approaches, for example; designing a shoe without unnecessary materials or features, choosing materials that fit within a circular economy model (e.g. bio-based/ plastic-free), and offering repair services that deal with wear and tear, ultimately prolonging the life of the product, and building in recyclability/ biodegradability into the initial design intention. Check out our list of sustainable design strategies.

Join forces with other shoe brands to develop solutions collaboratively. The Footwear Collective are open to accept new members.

Huge quantities of post-consumer shoe waste exist. This is a big problem that needs an equally big solution. The answer ultimately lies in drastically reducing the ‘need’ for non-circular and non-repairable new shoes. This could be done by raising awareness of the culture of consumerism like the Patagonia “Don’t buy this jacket” advert - honesty and transparency is attractive to consumers. The other option would be to encourage the use of existing shoes, for example, by advising consumers on how to care for and mend worn shoes.

References:

[1] (SMART, 2007)

[2] (SATRA, 2003 cited by James Lee and Rahimifard, 2012)

[4] (INTCO, 2015)

[5] (SMART, 2007)

[6] (Bally)